This early article about Photon appeared in the November 12, 1984 edition of

Advertising Age,

and is an exemplary piece of writing—detailed and accurate, with analysis, opinion, and personal experience.

[Transcribed

for the web from] Advertising Age, November 12, 1984

‘Disruption’

in Dallas

Writer

shot 28 times in 6½ minutes―lives!

By

KEVIN McMANUS

Someday in the future, perhaps during my lifetime, some genius will invent a game whose theme is the harmless but utterly realistic indulgence in all imaginable pleasures. Each player will be able to invent and partake in unlimited personal variations on that theme.

For example, my own variations would have names such as Time Machine, Pulitzer Prize, Wisdom, Money No Object, Invisibility, Flying and Marathon Upset.

Don’t ask me about format. However, I can assure you that this will not be a board game, nor a videogame, nor will it require a flat, grassy playing surface, cumbersome equipment, steroids, extraordinary intelligence or lots of money. Referees and reservations will be unnecessary, weather will be irrelevant and any number of people will be able to play together.

Perhaps it will be known as The Big Game, or Seventh Heaven, or simply It. “Nothing on the tube tonight, pet. Shall we play It?”

Alas, it seems unlikely that It’s creator is out there among the world’s scientists, inventors, engineers, biotechnologists and computer geeks. So, until he or she arrives on the scene, we will have to content ourselves with Photon.

In case you haven’t heard about it, Photon is a new game that, in terms of conceptual brilliance and socioeconomic wallop, may ultimately occupy a place between basketball and It.

(Then again, it may not. For my opinion, skip to the last section of the story.)

At present, you can play Photon in only one place—Dallas—but there will be franchised outlets doing business soon in many cities. The first New York City-area franchises are scheduled to open in January, but I didn’t want to wait that long to achieve my first “Photon experience.”

▪ ▪ ▪

In Dallas, two things took me aback immediately: How old Photon’s most frequent players are, and how seriously they regard the game.

Male, age 31: “Have you ever seen the movie ‘Rollerball’? [Describes movie: Futuristic setting, war, motorcycles, violence, gore.] The story is about a gentleman named Jonathan E. He was the best Rollerball player there was. That’s how I look upon myself. I want to be the Jonathan E. of Photon.”

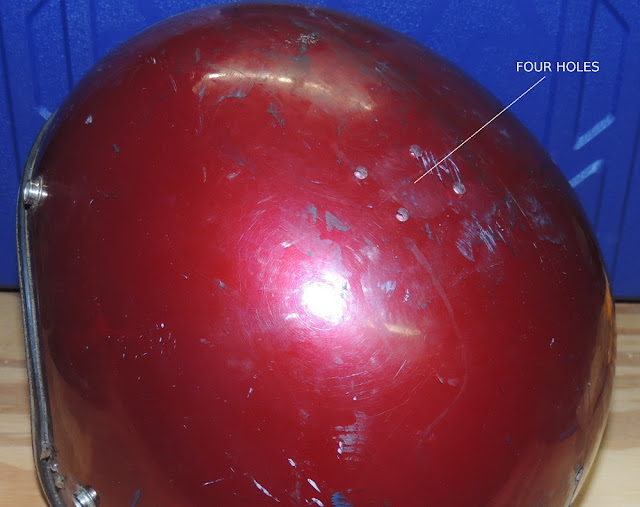

Zap!

A computer is about to register a "disruption" worth 10

points for the shooter and -10 to his victim. The Ad

Age darkroom made visible the beam of unseen infrared light.

Male, age 36: “We got people comin’ in here all the time that are ecstatic when they get 400 points. If I get 400 points, I’m embarrassed. If I don’t get at least 700, I don’t feel like I’ve really played well. I don’t score as many thousand-pointers as a lot of these guys do, but I don’t work at it as hard, either.”

Female, age 26: “My team is not abnormally good, but we’re very friendly. We cheer on the Jetsons because they always have real bad scores. We started giving them some training—helped them increase their accuracy. When you fire you have to be on target each time or you’re wasting shots. Don’t stand still when you’re getting shot.”

Male, age 26: “I like the idea of tournaments against other cities’ players. Absolutely. That’s the only way to determine who is the best. I intend to go to the first Photon that opens in Houston.”

▪ ▪ ▪

Yes, friend, Photon is a game in which adults run around firing guns at one another and accumulating points. (Kids play, too, but the median age of the serious Photon player is 24.) The guns are called phasers and they fire beams of infrared light. When the beam from player A’s phaser hits its target—either the chest piece or helmet of player B—a radio signal is transmitted from a microcomputer implanted in B’s chest piece to a central computer at the edge of the playing field. The central computer adds 10 points to A’s score and subtracts 10 points from B’s.

Once “disrupted” by A’s shot (Photon spokesmen discourage use of the word “kill” in this context), B is unable to fire his own phaser for a few seconds. But he can still be hit again by enemy fire and lose more points. B’s best option here is to seek cover.

Players distinguish opponents from teammates on the near-dark playing field by the colored lights on everyone’s helmet. There are two teams, green and red, the player strength of each depending on how many customers are waiting in line when a new game starts. (Games vary from one-on-one to 10-on-10.) You know an opponent has been disrupted when you see his helmet lights turn yellow and start blinking. When you’ve been disrupted, you hear a certain noise inside your helmet.

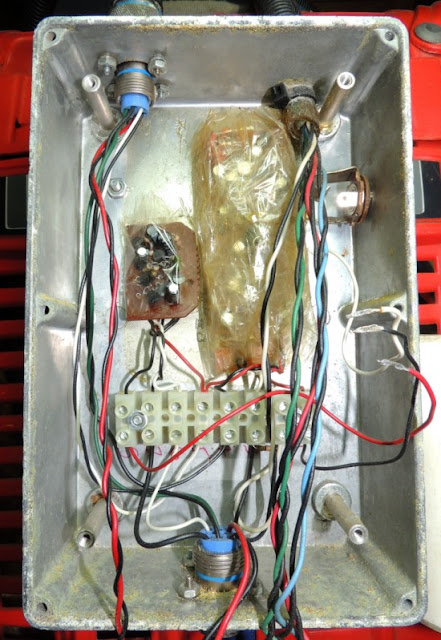

Photon

junkie Beathan awaits his next

fix.

Each game lasts 6½ minutes; at the end, players leave the field through a doorway that leads to a room where they remove their gear and check their scores in a tv monitor.

There are more particulars that circumscribe play, and the most important of them are the design of the playing field, the team bases at either end of it and the 5-ft. rule.

The playing field is a room roughly the size of a tennis court, with a 16-ft. ceiling. In it is an asymmetric arrangement of pillars, partitions, hallways, stairways, ramps, platforms, catwalks, and rows of variously-sized, open-ended chambers that players refer to as “the catacombs.” The motif is meant to evoke certain settings in the movies “Star Wars” and “Tron.” In the middle of the room is an observation deck that patrons reach via a stairway and a short catwalk.

At either end of the room is a rectangular, floor-to-ceiling column with a pyramidal, ever-blinking lamp attached about halfway up. This is known as the base, and both teams have one. At the foot of the base, between the column and the wall, teammates muster before each game.

Once a game begins, each player’s principal goal is to shoot the opponent’s base three times without interruption. When the third shot registers, the player gets 200 points. You can shoot your opponent’s base as often as you want, but the computer awards you those 200 points only once per game.

The 5-ft. rule, which refers to the distance between opposing players, is meant to keep hostile warriors from intentionally engaging in physical contact. Otherwise, a player can move about freely on the field, or can spend the whole game hiding.

▪ ▪ ▪

Each new player is required to buy, for $3.50, a Photon ID card that is to be honored at all franchises, forever. (So I’m told.) Game tickets cost another $3 apiece. Before posing for the ID photo, you fill out a release form that asks your name, address, phone number and age. When you play, you wear your bar-coded card in a slot attached to your chest piece, or “pod” (Remember? the device with the implanted microcomputer?).

How clever. Photon’s main computer can match your personal data with your playing habits. How often you come in, how many games you play per visit and with whom, how well you score. Once the franchisees’ computers start feeding their customer data to headquarters in Dallas, Photon Amusements’ marketing whizzes will be able to put it all together 20 different ways, analyze it, identify trends and continually fine-tune their national marketing strategy.

“We want to be able to keep a step ahead of customers’ whims,” said Dan Allen, the company’s 30-year-old marketing director, who formerly served in the same capacity at Domino’s Pizza.

Wait—there’s more.

Precise customer data, important to any business enterprise, is especially vital to Photon because its strategists aim to push the game into the realm of competitive sport. In that effort, individual and team statistics—fresh and exhaustive—are all-important. For Photon, gaining access to these statistics would seem to be a matter of writing the proper software. Zap—it’s done.

A year from now, when several franchises have been operating awhile, sports fans might actually be able to follow teams in a national Photon league. That, at any rate, is the dream of George Carter III, the man who conceived and helped design the game.

“There’s no distinction between a game and a sport,” said Mr. Carter, 39, Photon’s president. “Kids go out and play basketball on the street, for fun. But then people also play basketball as a true professional sport. So It think Photon could be both. All the elements of sport exist in this game.”

Somewhat more grandiosely, he pronounces, “Traditional games will probably dwindle. You’re seeing the first glimpse of a true future sport.”

Since Photon opened in April, approximately 15,000 people have played. At least 500 have become regulars who show up once a week, usually to play more than one game. Of them, 60 have joined the 12-team league that formed in July.

▪ ▪ ▪

I played my first game on a Tuesday afternoon. The doors had just opened and customers were so sparse that there were long (10 to 20 minute) intervals between games. Up on the observation deck I’d met a fellow named Victor Egly, a 34-year-old musician, who had brought his 13-year-old son, Jason, to play. Victor said he was there as an observer, but he soon let me talk him into playing one game, on the condition that I buy his ticket.

We were both put on the green team, along with another guy. On the red side were Jason, who would be playing his third game, and two other kids. The 18 lbs. of battle gear—battery belt, pod, and helmet—felt heavy, but did not much inhibit my walking, running or crouching movements.

The phaser, which was hooked up to my pod by a Photon attendant, was metal-and-plastic, with a springy trigger and a long barrel. When I pointed it, a red light would flash on at the barrel’s rear end whenever the weapon was focused on a target. If I fired and hit the target, I would hear a sound inside my helmet—errarrarrarr—much like the sound a car engine makes when you try to start it on a dying battery. When I fired and missed, or when someone shot me, I heard two different sounds that I can describe only as synthesized, futuristic and altogether goofy.

An attendant ushered our team through a door to our station beneath the green base. To ensure that our phasers were working properly we fired at our base and at the helmets of the red players, who were being led to their base. Then a female voice could be heard from above: “Welcome, Photon warriors. Commence strategic maneuvers at audible command signal. Five, four, three, two, one. . . begin.” Our team scattered and I was on my own.

It took me only about 30 seconds to discover what marketing vp Dan Allen meant when he told me size and strength are insignificant in this game compared to cunning, agility and experience. Ghostlike, the red kids would appear suddenly, zap me and flee. Many times, too, I would hear the noise in my helmet telling me I’d been disrupted, but would be unable to figure out which direction the shots came from. Eventually I’d look up and see red lights bobbing on a catwalk. The 6½ minutes seemed more like 15; at no time during the game did I feel silly. Afterward, I confess, I wanted to play more.

I ended up with a minus-80, which would have been a minus-280 had I not gotten the red base. Victor scored something like minus-200 and, worse, still was breathing hard 10 minutes after we removed our gear. “I felt my knees getting a little weak there toward the end,” he said. “Cigarets, you know.”

Victor had been confused by the field’s layout. “I went across that bridge there and came down in that little maze, and after that I never got it together again to see where I was. Also, I never got the sounds down right.

“I kept thinking the sounds were coming from my gun, when actually there was someone standing behind me, just blowing my brains away.”

Jason, who had gotten a 270, joined us. I asked him what was the secret to scoring well. “Learning how to hide real good,” he said. “Learning what the field looks like. You need to know real good how to aim the gun ’cause it doesn’t really have a good aim thing on it. It’s pretty fat.”

Did Jason know about the Photon league? “I just heard about it,” he said. “I think it’d be pretty neat to enter because if you win you get trophies and hats and stuff.”

▪ ▪ ▪

Wednesday night. League night.

The members of Wolf Pack, a high-scoring and popular team, exuberant over a 1900-point victory, discuss strategy between games.

“I’m gonna take the base this time, but you need to be in there because we had ’em making single-man runs underneath the ramp.”

“You know how to take ’em out from there? You just go around the front, shoot ’em three times, lean in and clear your gun.”

“I was hittin’ from up top over the balcony. You can hit ’em from there if you just get the right angle on it, lean far enough over and don’t fall out.”

“That one guy in the blue shirt is maybe a 200-average player. So if you see him over there you’ll be able to take him out.”

Wolf Pack is comprised of the following players:

Hope Meredith, 26, dancer and free-lance choreographer. Hope wears her blond hair in a long braid and spends many idle moments doing stretching exercises. “Playing Photon isn’t really a substitute for any other activity. It’s completely extracurricular. If I weren’t doing this, I’d be dancing.”

Michael Boswell, 26, electrical engineer. “I’m just a gamer; I’ll play anything.” How does Photon stack up against videogames? “In video parlors you’re playing against a computer, and here you’re playing against a person. It makes all the difference in the world.”

Wolf

Pack teammates muster before league night battle.

Jim Traylor, 26, furniture salesman. Jim used to work next door to Photon, came in one day out of curiosity, now is “totally addicted,” plays 15 to 20 games each week. “This can be an expensive habit if you play as much as I do. I work 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day. I work and work and work and play Photon.”

David White, 27, Photon attendant. Before joining Photon, David worked for five years as a singer for a singing telegram company. He would love to manage a Photon franchise. “It’s a little bit like Six Flags, IBM and a singing telegram company all rolled into one.”

Beathan, 31. An ex-biker (in Dallas) and ex-tank commander (Vietnam), he describes himself as a starving artist and told me not to mention his last name here. He wears shoulder-length black hair and a Fu Manchu mustache. Probably the only true Photon junkie, he plays game after game, six days a week. “One day five years from now I plan to be sitting in a Photon stadium as big as Texas Stadium with 50,000 people chanting my name.”

▪ ▪ ▪

As of last October, Photon Amusements had signed deals with franchisees in Southern California, New Jersey, Houston, Chicago, Phoenix and Denver. Both Canada and the U.K. were under master franchises, and Photon had signed a tentative agreement with a group based in Taiwan and Hong Kong that will be the master franchisee in the Far East.

In New York, a group of businessmen has united as a Photon franchisee syndicate. They plan to build a minimum of 10 playing fields (two fields per outlet, in most cases) in the New York City-Long Island-Connecticut area. Gary Adornato, formerly a broker with Shearson/American Express, is chairman of the syndicate. Adornato walked into the Dallas Photon in the waning hours of league night, and we talked.

He told me about the other syndicate board members. “These are people who are not usually followers of fashion,” he said. “They are each principals of their own firm; each of the firms is a fairly significant entity in its field of expertise. And they’ve all come together as extremely strong proponents of what first seemed to be a fairly esoteric concept.” Photon franchisees pay a fee of $50,000 per unit, plus 5% of each month’s gross. The cost to build and equip one unit is between $300,000 and $350,000.

I asked Adornato if his group’s franchises would differ much from the 10,000-sq.-ft. Dallas unit, which is actually an operating prototype. “Photon is a social activity,” he said. “You come out and you’re compelled to share your experience. In keeping with that, we’re going to use 30,000-sq.-ft. sites with four major components.” These will be food and beverages, Photon merchandise (cups, t-shirts, hats, etc.), entertainment (possibly videogames) and a locker room.

A locker room? Will customers actually want to shower and change clothes after playing Photon, as they do at a health club? “Think about it,” said Adornato, a beefy guy who wore the beginnings of a beard that evening. “You’re in New York—it’s December—it’s snowing outside. You’ve played four games and you’re sweaty and your pants are tacky. And you’re going to get in your car and drive home that way?”

All the extras—food, merchandise, the locker room—are going to contribute to the “Photon experience,” said Adornato. “We want it to be an evening’s entertainment. You come out for three or four hours and you may play three or four games, but there’ll be other environmental things you’ll want to do as part of it—Photon being the focus.”

Had he played the game yet? “No more than 40 or 50 times,” he said. “I play a little too sporadically to get better, but I feel I’m more in control of the environment now. There’s a very definite learning curve in this game.”

▪ ▪ ▪

Photon’s rules, equipment, playing field and supporting software were designed during a 10-month period beginning in May, 1983. That’s when George Carter started to act upon his notion that people would find enormous pleasure in playing a game that pitted human competitors against one another in “Star Wars” and “Tron”-inspired battles.

Carter, who had owned go-cart tracks and three Chaparral Grand Prix miniature race tracks, didn’t have the technical know-how to bring his idea to life. So he found someone who did: Jim Dooley, an electronic design contractor. Dooley, then 35, had designed such things as an underwater vehicle for inspecting pipelines, an electronic pipe-measuring device and an integrated-circuit tester.

After the first prototype equipment was built, Carter, Dooley and others spent hour after hour playing the game, trying to figure out how to make it fun and safe and challenging. Their constant tinkering yielded the components of the game as it’s played today. Sometime between now and Christmas, new player gear and computer software will replace the equipment that has been in place since April, and there will be some rule adjustments. “All the electronics will be more reliable,” said Dooley. “And we’ll be able to play 40 players at a time instead of 20.”

The fat, bearded Mr. Dooley is as casual and unkempt as his boss Mr. Carter is natty. While a recent eye operation keeps Mr. Carter from playing much these days, Mr. Dooley’s game continually improves with constant practice. He claims to be the oldest player who’s ever scored more than 1,000 points in a game, and he is at work on a book about Photon strategy.

Photon is not only Mr. Dooley’s most complex project so far, it is the only one in which he has chosen to stay involved after the initial work was done. “I’ll probably hang around this thing for quite a while,” he told me one afternoon while he was hanging around waiting for a game to start. “I’m trying to get one of my own franchises.”

▪ ▪ ▪

George Carter, his franchisees and many other individuals are going to make big money over the next few years, but I strongly doubt that Photon will ever achieve the status of a national sport. Certainly it is a brilliant, wonderfully executed concept, and great fun to play. But unlike basketball—to which Carter compared it—Photon is expensive, too expensive for most players to practice a lot.

Think about it. If court time cost $3 per six minutes, how many basketball professionals—or even accomplished amateurs—would there be?

Furthermore, I’m automatically suspicious of any new enterprise that receives the extensive, uncritical publicity that Photon has gotten since the Dallas outlet opened last April. Forbes, Inc., Venture, “Today,” “Entertainment Tonight” and innumerable daily newspapers and radio shows have devoted space and airtime to George Carter’s new game.

Newsweek gave it an entire page, observing that “the biggest risk in Photon may be its addictive nature; some devotees manage to spend as much as $100 per day.” I wonder how many such devotees exist. I didn’t meet any when I was there. (Photon junkie Beathan plays for free, as a member of the company’s promotional team.)

You can expect a second wave of media coverage to begin in January, as Photon franchises begin opening around the country. You can expect to hear about long lines at all the new outlets. Eventually you may even read about a national Photon tournament.

But don’t believe all the hype about traditional games dwindling because of this brand-new one. At three bucks a pop, the Photon experience is hardly a sporting proposition for the inhabitants of this planet. #